Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere review — a quiet, patient portrait of making Nebraska

Aug, 31 2025

Aug, 31 2025

What happens when the demos are the album?

The great twist in the story of Nebraska is simple: the rough tape was supposed to be a sketch, not the final record. Yet that haunted cassette, recorded alone at home, became one of rock’s most unlikely landmarks. Scott Cooper’s Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere leans into that knot—how a private set of songs, spare and raw, refused to be smoothed out by a big studio and a hot band.

The film adapts Warren Zanes’ 2023 book about that short, intense window in 1982, when Bruce was cutting arena-sized songs with the E Street Band while also tracking these small, aching stories by himself. On screen, that split becomes the tension line: spectacle versus intimacy, volume versus whisper, the showman versus the man trying to understand his own darkness. It’s a tight frame, and Cooper keeps the focus close, often claustrophobically so.

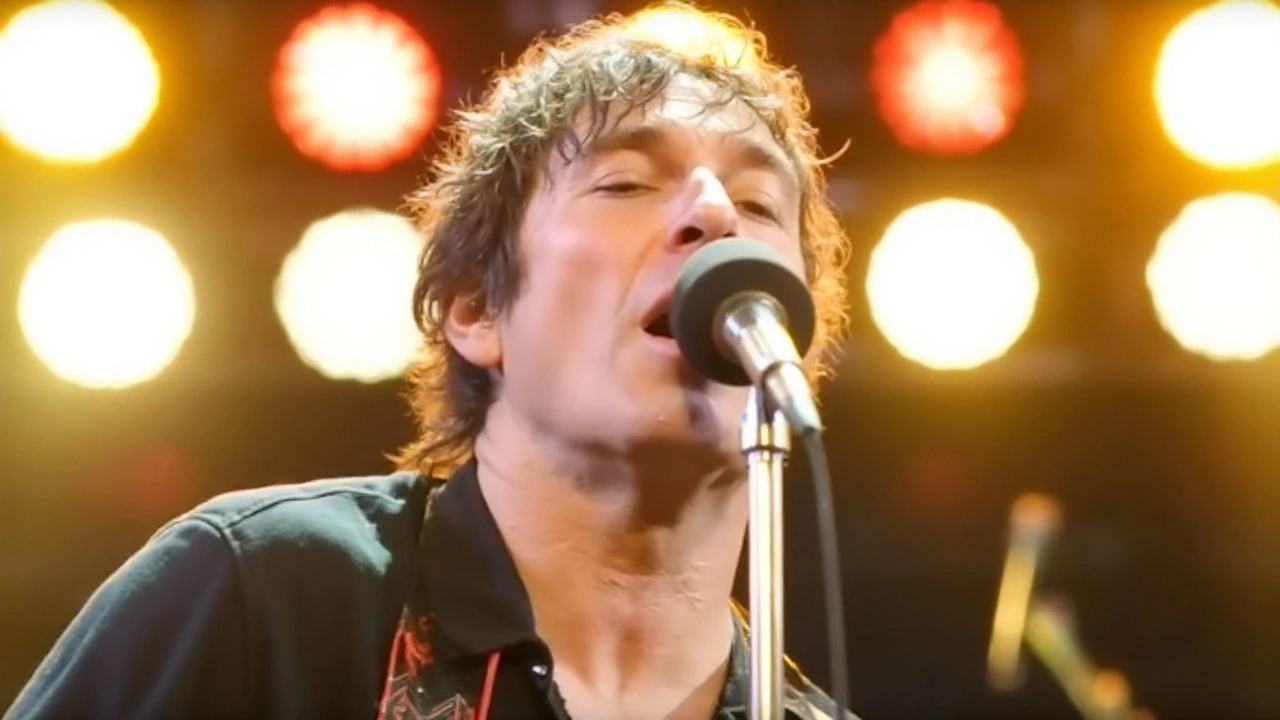

Jeremy Allen White plays the musician not as a myth but as a guy who cannot shake the weight in his chest. Early scenes make that clear, even as they flirt with biopic shorthand—sudden inspiration, scrawled lyrics, long stares into the middle distance. We get snatches of childhood through flashbacks, memories cutting in like intrusive thoughts. There’s a neon glow to the initial romance scenes, a nostalgic sheen that suggests how the legend is usually told. Then the film settles, pares back the shine, and starts to breathe.

That shift is where it finds itself. The middle stretch drops the rock-god haze and becomes a study of process. It shows the grind of trying and failing to recreate the feel of a bedroom take inside a professional studio. Fancy microphones, a room full of talent, endless takes—and yet the magic keeps slipping away. You hear a guitar line that’s technically cleaner but emotionally thinner. You see the gap between “good” and “right.”

Jeremy Strong, as manager and producer John Landau, is the film’s quiet spine. He listens. He doesn’t lecture. He protects the work without fanning the myth. Strong plays him with gentle understatement—small smiles, calm hands, eyes that say, “I’m here, keep going.” It’s the softest performance he’s given on screen, and it feels exactly right for someone tasked with guiding an artist who is both prolific and fragile.

The early going, to be fair, wobbles. It leans on the standard toolkit: cross-cut flashbacks, montage, the trope of the inspired loner scribbling masterpieces in one sitting. But Pamela Martin’s editing gradually trades speed for patience. Scenes get longer. Reactions matter as much as lines. The camera starts to sit with silence, and when it does, the movie begins to hum at the same frequency as the songs it’s portraying.

White’s work deepens the same way. He begins like an outline—a clenched jaw, a low voice, that familiar working-class snarl—and then his face starts doing the heavy lifting. There’s a hesitant rhythm to his speech, a stammer that fits a man who is unsure what to say and afraid to say the wrong thing. He listens in scenes where earlier he would have performed. You can see him hold back and then let truth slip out in tiny, nervous bursts. It’s a smart piece of acting: the imitation fades, the person shows up.

Strong’s restraint pairs with that beautifully. There’s no grand speech to save the day, no big “producer as savior” moment. Instead we get presence. He’s there to steady the room when an idea collapses. He’s there to absorb a bad take without making it worse. He’s the friend who knows when to blink and when to say, “That’s the one.” That emotional economy turns their scenes into the film’s heartbeat.

Paul Walter Hauser and Stephen Graham pop in with sharp supporting turns. The roles are small by design—this is not a hangout film about the whole band or a label drama about executives—but they leave marks. The supporting cast helps fill out the world: the road people, the studio rats, the partners and friends who orbit a famous person’s work and try not to get burned by the heat.

Cooper, who has a feel for American melancholy from earlier work like Crazy Heart, keeps the tone sober. The palette is winter-gray and motel-brown. Rooms feel cramped. The nights are long. Even when the E Street energy briefly blasts in, the camera holds to the face, not the crowd. You sense a director refusing to give the audience the big sugar rush, because the story is about everything that happens when the stage lights go dark.

Sound is the axis. The film trusts the scratch of strings, the tick of a metronome, the nervous breath before a line lands. It never drowns the room in hits. You catch a phrase, a melody, the shape of a chorus—then it cuts to the moment of doubt after the take, when somebody asks, “Is that it?” That’s where Nebraska lives: in the uncertainty that the true version is not the most polished one, not the loudest one, not the one that will sell the most tickets.

There’s a recurring idea here about honesty. The studio version of these songs can’t beat the tape from home, not because the players aren’t brilliant, but because the mood won’t come back once the lights are up. The camera sticks with that contradiction until the obvious answer starts to feel brave: maybe you release the tape. Maybe the demo is the record. The movie isn’t out to turn that decision into a triumphalist moment. It lets it feel strange, even scary—an artist choosing discomfort over safety.

The narrative never lingers long on mythmaking. We don’t get a parade of celebrity cameos or a greatest-hits singalong. This is closer to a creative case study than a victory lap. Compared with the recent wave of musician dramas that race from childhood to superstardom, Cooper picks one room, one era, and stays there. Think less jukebox blaze, more sustained note.

That isn’t to say the film is austere to a fault. There’s romance—tender in places, breathless in others—but it’s there to echo the push-pull inside the music. The early stylized glow softens into something rawer as the story tightens. When the relationship gets messy, the visuals cool, and the chronology loosens, like memory itself is doing the editing.

Flashbacks are used with a clear purpose. They’re not history lessons; they’re triggers. A fragment of a childhood home. A look from a parent. A long car ride that won’t end. The movie doesn’t spoon-feed a diagnosis, but it shows how the past keeps interrupting the present, especially when the present is quiet enough to hear it.

If you’re coming for a celebration of stadium rock, this will feel intentionally underpowered. The scale is small because Nebraska was small—bare voice, spare guitar, and stories about people who felt backed into corners. The movie honors that scale. It’s more motel hallway than arena tunnel, more two-lane night drive than festival fireworks.

White’s physical choices are worth calling out. The hunched shoulders. The way he grips a guitar like it might slip. The cautious walk into a studio where everyone expects greatness and he’s carrying songs that are dark and stubborn. He sells the fear that the thing he made alone might die under the bright lights. Then he sells the relief when someone else hears what he hears.

Strong keeps finding little ways to say, “I value the person, not the product.” It’s there in how he watches a take all the way through. It’s there in his refusal to panic when a plan stalls. His Landau understands that management is often about absorbing stress and letting an artist keep the headspace to make something difficult. That kind of care doesn’t usually photograph well. Here, it does.

The supporting players never crowd the central line, yet they fill out the ecosystem around it—techs fussing over cables, a drummer waiting for a call that may not come, friends making jokes to break tension. Those beats give the film texture. You feel the community that builds the machine, even when the machine isn’t the right tool for the job.

Technically, the film is tidy. Martin’s edit keeps the rhythm steady; it slows when the music breathes and tightens when the studio clocks start to matter. The camera favors close-ups and practical light. Colors lean into the era without winking at it. You can tell Cooper and his team want to disappear behind the performances and the sound.

There’s a small but pointed thread about commerce. How do you package a record that whispers? How do you sell songs about people who lose? The film doesn’t mount a screed against the industry. It simply shows the awkward meetings, the cautious nods, the long pauses when someone admits that art and market won’t meet in the middle this time. That friction gives the later scenes their quiet charge.

The script has its lumps—some on-the-nose lines, a few familiar setups—but it also gives space for those tiny, human moments that stick. A rehearsal that dies in the first verse. A joke that doesn’t land. A look between two friends that says, “We’ll try again tomorrow.” Those bits build a believable world, and they pull the film away from the thin air of legend.

And then there’s the music itself, which the film treats with care. The famous “Starkweather” origin for the title track flickers by, not as trivia but as proof that the stories came from a place of real unease. Violence, guilt, desperation—these are tough materials. The movie doesn’t glamorize them. It frames them as the hard truth the artist won’t look away from, even when he wishes he could.

As a viewing experience, it’s more candlelight than spotlight. You feel the time pass. You feel the weight of false starts and the relief of small breakthroughs. That patience may test some audiences, but it matches the album at the center of the story. If Nebraska is a whisper, the film gets closer to a whisper than most music biopics dare.

Early reactions back that up. The first wave of critics calls it effective and moving, if a bit stiff in places—“overwritten” is a word you’ll see. The IMDb score sits in the low-to-mid sixes so far. That tracks. This is a made-on-purpose mood piece, not a juggernaut. It will reward viewers who are curious about the work behind a work, who don’t mind watching for the small turn in a face rather than the big finale.

The runtime lands at two hours, which feels right. It gives the film time to wobble, recalibrate, and then play out its quiet second-half confidence. The release is set for October 24, 2025, which positions it in that tricky fall window where small films can either disappear or gather word-of-mouth. Awards talk will likely orbit the two leads, especially Strong’s soft-focus precision and White’s late-bloom control.

For fans, there’s value in seeing the emotional logic behind a famous left turn. For newcomers, there’s an accessible story about a worker trying to keep faith with himself when the easy path would be louder and brighter. The movie keeps reminding us: the point of these songs was not to sound big. The point was to sound true.

It’s worth saying out loud: the film never equals the album it honors. How could it? Nebraska is lightning in a cassette. But this is a respectful companion piece, a study in tone and doubt, and a portrait of a relationship that helped an artist choose the scarier road. It finds drama in restraint, and it trusts the audience to meet it halfway.

That last choice matters. This isn’t a museum tour for the faithful or a myth-polishing exercise. It’s a slow, careful look at what it costs to risk the small thing in a big world. And it leaves you with the sound that started it all: a guitar, a voice, a room that hears a man telling the truth. That’s as close as cinema can get to the paradox that made Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska endure.

Performances, craft, and what lingers

White grows from mimic to actor by paying attention—letting embarrassment creep in, letting anger recede, letting fear flicker. Strong builds a counterpoint made of steadiness and care. Together they anchor the film’s best scenes, the ones where nothing “happens” except a choice, and that’s enough.

Cooper’s direction keeps clichés at bay when it matters most. He’s comfortable with silence, and he trusts the room. Martin’s cuts give actors breathing space, then push forward before stillness turns stagnant. The look is unfussy. The sound strategy is obvious but right: clear and close, never indulgent, rarely bombastic.

If the opening feels familiar—and it does—the film earns its later gravity by working like the songs work: simple parts, carefully placed, held for just long enough. It is a meditative character piece about a person who, for all his fame, is most interesting when the amps are off and the door is closed.

So where does that leave the audience? With a drama that is smaller than the legend but larger than the clichés. With acting that asks to be watched, not just heard. With an idea that won’t go away: sometimes the truest version is the first one, and the bravest decision is to let it be.

Barry Hall

August 31, 2025 AT 17:43The film’s quiet focus lets the Nebraska demos breathe, and that’s exactly what fans need :)

abi rama

September 10, 2025 AT 20:07Seeing the way the camera lingers on small gestures, you get a sense of how fragile the creative process can be. The patience in those lingering shots mirrors the patience Bruce showed while listening to his own recordings. It’s a reminder that sometimes the biggest breakthroughs happen in the quietest rooms.

Megan Riley

September 20, 2025 AT 22:31What really stands out is the supportive environment on set, which reminds us that even legends need a steady hand; the film shows that without the right guidance, a raw demo could easily get lost in the studio’s polish. It’s like a coach whispering, "keep the edge," while the rest of the world shouts for perfection, and that contrast is beautifully captured. Also, notice how the editing never rushes - it lets the tension build organically, which is exactly what makes the story feel authentic, even if some of the dialogue feels a little forced at times. :)

Lester Focke

October 1, 2025 AT 00:54Cooper’s decision to treat the demo recordings as the narrative spine is a study in artistic fidelity. By refusing the conventional biopic gloss, he foregrounds the tension between commercial expectation and private creation. The camera hovers in the cramped studio, capturing the micro‑movements of White’s hands as if they were the only instruments that mattered. Each lingering shot of a muted guitar string becomes a meditation on the impossibility of reproducing a moment’s rawness in a polished environment. The editing rhythm, deliberate and unhurried, mirrors the pacing of the original Nebraska tracks, which themselves were built on minimalist arrangements. Strong’s portrayal of John Landau is deliberately restrained, offering a counterpoint that underscores the necessity of a steadying presence without ever eclipsing the artist’s voice. This restraint is not a lack of emotion but a calculated economy that aligns with the film’s broader aesthetic of subtraction. The supporting roles, though brief, function as ecological markers, reminding the viewer of the larger machinery that surrounds any solo endeavour. In particular, the cameo of Stephen Graham, though limited, injects a glimpse of the industry’s indifferent bustle, contrasting sharply with the interior solitude. The sound design eschews grand orchestration, instead foregrounding the scrape of strings, the click of a metronome, and the breath of the performer, thereby reinstating the listener to the original listening experience. This auditory fidelity is reinforced by the choice to limit background scoring, allowing the songs themselves to occupy the emotional space. Cooper’s use of natural lighting, set in winter‑gray tones, serves as a visual metaphor for the bleak honesty contained within the lyrics. The cinematography refuses the spectacle of stage lighting, opting instead for the dim, amber glow of a makeshift home studio. Such visual choices compel the audience to confront the uneasy truth that artistic authenticity often resides in imperfections. The film thereby becomes an elegy to the notion that the first, unvarnished take can hold more truth than any subsequent refinement. In sum, the piece offers a rigorous, almost scholarly, contemplation of how a modest cassette could reshape the trajectory of an iconic career.

Naveen Kumar Lokanatha

October 11, 2025 AT 03:18I think the film succeeds in showing that a supportive manager can be almost invisible yet pivotal. The subtle glances between White and Strong convey trust without needing exposition, and that’s a lesson for anyone working behind the scenes. It’s refreshing to see a mentor figure portrayed with such quiet dignity.

Alastair Moreton

October 21, 2025 AT 05:42Honestly, the whole thing feels a bit pretentious-like it’s trying too hard to be an art‑house flick. The pacing drags, and I found myself checking the clock more than the storyline. Still, the performances are decent enough to keep me watching.

Surya Shrestha

October 31, 2025 AT 07:06The aesthetic choices, particularly the monochrome palette and restrained framing, elevate the narrative beyond mere documentation; they imbue the film with a gravitas befitting an examination of artistic integrity. By eschewing ornamental excess, the director invites the audience to contemplate the ontological essence of the recording process itself.

Rahul kumar

November 10, 2025 AT 09:30what i love most is how the film breaks down the studio gear setup without going overboard; it actually helps newbies understand why a simple mic can sound better than a fancy array if used right. also the pacing feels more natural than i expected, kinda like a chaat stall conversation-fast enough to keep you hooked but with plenty of spice.

mary oconnell

November 20, 2025 AT 11:54One could argue that the film’s deliberate minimalism serves as a dialectical critique of the commodification of nostalgia, effectively positioning the Nebraska sessions as a locus of epistemological resistance. In other words, it’s less about Bruce’s personal demons and more about the industry’s perpetual yearning for a mythic simplicity that never truly existed.

Michael Laffitte

November 30, 2025 AT 14:17Wow, that just blew my mind! It’s like the director took a quiet whisper and turned it into an epic saga-totally dramatic and honestly, I’m loving every second of this deep dive.

sahil jain

December 10, 2025 AT 16:41In the end, the movie reminds us that sometimes the most powerful art comes from the simplest moments, and that’s a lesson worth taking with us.